A Curious Beginning: Europe Meets the East

Imagine a time when silk was as rare as stardust in Europe, and porcelain was considered more valuable than gold. That’s the world Marco Polo stepped into when he returned from Yuan Dynasty China in the late 13th century. His tales of the East weren’t just dinner-party anecdotes—they sparked a fascination that would echo for centuries.

This wasn’t just wanderlust. It was the beginning of a cultural phenomenon later coined as Chinoiserie—a term that only entered academic parlance in the 19th century but whose aesthetic impact had already been shaping European interiors for hundreds of years. From the baroque excesses of France to the pastoral tastes of England, Europeans didn’t just import goods from China—they reimagined what “China” was.

| “They make fine and beautiful pottery of clay, which is made into vessels of every sort, and painted with figures of many colors.” | _1757381394264.jpg) |

| MARCO POLO RETURNS |

Here’s the kicker: “Chinese style,” or what we now call Chinoiserie, was less about authentic representation and more about Western imagination. Blue-and-white porcelain, intricate gardens, and misty mountains in ink wash were only part of the story. These motifs were filtered through a lens of fantasy and desire, creating a version of China that never existed. In essence, Chinoiserie was Europe dreaming of the East—half reality, half fairy tale.

According to the discussion in "The Language of Ornament": European countries, through their "East India Company", imported a large number of luxury goods from the Far East regions such as China and Japan. Europeans imitated and recreated these exotic items, thereby giving rise to a decorative art style known as "Chinoiserie" (Chinese style), which reflects the romantic fantasies of Europeans about the Eastern world.

_1757381629929.jpg) CHINESE BLUE AND WHITE PORCELAIN

CHINESE BLUE AND WHITE PORCELAIN

As explored in the USC Scalar digital project, this cultural construction was deeply rooted in exoticism and objectification, forming a Western lens that turned Chinese culture into decorative myth.

The Rise of Chinoiserie in 17th and 18th Century Europe

Chinoiserie truly hit its stride in the 17th century when maritime trade between Europe and East Asia began booming. As the Dutch East India Company and other trading empires brought silk, lacquerware, tea, and porcelain to European ports, these items quickly became status symbols among the elite.

_1757381933554.jpg) FRENCH ROCOCO ROOM DECORATED WITH CHINOISERIE

FRENCH ROCOCO ROOM DECORATED WITH CHINOISERIE

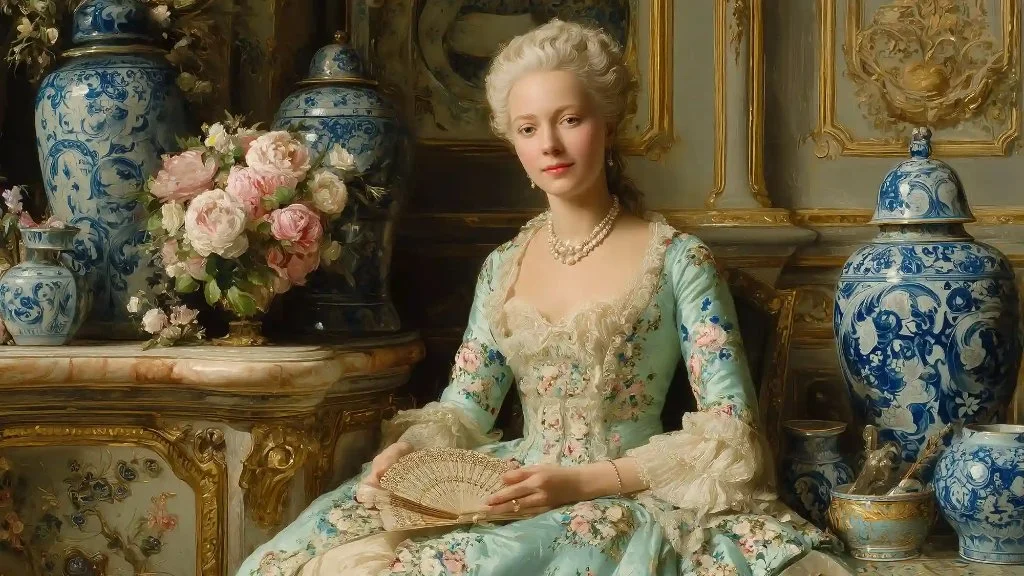

French aristocrats went bananas for it. At Versailles, Louis XV had entire rooms furnished with lacquer panels and porcelain vases. His mistress Madame de Pompadour was obsessed with Chinese fashion and often posed with Chinese fans and silk garments in portraits. Across the Channel, English nobles began collecting Chinese screens and integrating Chinese latticework into architecture. Chinoiserie became the go-to style for those who wanted to flex their wealth with a side of exoticism.

| With Chinese fan and silk, embodying Chinoiserie’s allure—admired by elites, dismissed by some as excess | _1757382096169.jpg) CHINESE FAN AND SILK CHINESE FAN AND SILK |

But it wasn't all smooth sailing. Some Europeans viewed Chinoiserie as frivolous—like interior design's version of chasing butterflies. It was novel, opulent, even bizarre. Yet, the popularity of these “oriental” flourishes couldn’t be denied.

| Chinese lattice windows and décor, reflecting the fusion of European elegance | _1757382404156.jpg) |

| WITH CHINESE DECOR |

The NGV's “Chinoiserie: Asia in Europe 1620–1840” exhibition provides rare insights into how such aesthetic tastes materialized into over 180 physical artifacts that fused imagination with commerce, from French Saint-Cloud porcelain to English hand-painted silk.

_1757382600082.jpg) CHINOISERIE PORCELAIN AND LACQUERWARE

CHINOISERIE PORCELAIN AND LACQUERWARE

The German Twist: Palaces, Porcelain, and Prestige

While France and England were early adopters, the German-speaking states were late bloomers in the Chinoiserie game. Still, they brought their A-game when they showed up.

| Showcased Europe's largest porcelain collection in 1719 | _1757382933562.jpg) |

| DRESDEN PALACE WITH PORCELAIN |

Take Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland. After visiting the famed Trianon de Porcelaine at Versailles, he decided to go big—or go home. In 1719, he ordered the transformation of a Dresden palace into a full-blown “Japanese” palace, housing what would become Europe’s largest porcelain collection. This moment fused politics, luxury, and fantasy.

_1757383156420.jpg) PORCELAIN WITH GOLD EMBELLISHMENTS

PORCELAIN WITH GOLD EMBELLISHMENTS

This wasn't about authenticity. It was about awe. In a weird twist of fate, Chinese ceramics—known for their humble elegance—were often adorned with gold embellishments in Europe, all to suit aristocratic tastes. The German version of Chinoiserie was loud, proud, and unapologetically baroque.

Lost in Translation: The Fantasy of China

Here’s the thing: most Europeans had no idea what real Chinese culture was like. They were creating an imagined version of the East, filled with dragons, pagodas, and whimsical flora.

| The illustration style of the "Oriental world" | _1757383283527.jpg) |

| WESTERN FANTASY LANDSCAPE |

The USC analysis clearly articulates this as “objectification through aesthetic reassembly”, emphasizing how Chinese identity was filtered through imperialist notions of superiority and fantasy [USC Scalar].

This “creative misreading” wasn’t always innocent. Sometimes, it reflected colonial fantasies and a desire to exoticize the unfamiliar. Yet beneath it all was a genuine curiosity, a longing to understand and connect with something distant and mysterious.

| European art’s exoticized adaptation of Chinese motifs through an imperialist lens. | _1757385290396.jpg) |

| IMPERIALIST REINTERPRETATION OF CHINESE |

It was a double fantasy: East imagining West, West imagining East. The silk was real. The porcelain was real. But the China that Europeans crafted in their salons and palaces? That was a dream wrapped in lacquer and gold.

Chinoiserie in the Victorian Era: Mass Market, Mass Appeal

Fast-forward to the 19th century. Industrialization was in full swing, and suddenly, Chinoiserie wasn’t just for royals. Middle-class families could now decorate their parlors with bamboo furniture and dragon-embossed wallpaper, thanks to cheaper production methods.

_1757384122294.jpg) PARLOR WITH BAMBOO FURNITURE

PARLOR WITH BAMBOO FURNITURE

Victorian England embraced Chinoiserie as part of its global empire aesthetic. Think teahouses with curved roofs, opium dens with red lanterns, and drawing rooms filled with Chinese fans and embroidered cushions. If it looked vaguely “Eastern,” it was in.

_1757397098765.jpg) TEAHOUSE WITH CURVED ROOF

TEAHOUSE WITH CURVED ROOF

Critics scoffed. To them, it was tacky—an interior design free-for-all. But for many, it was a way to travel without leaving home, to feel worldly and cultured through décor. Chinoiserie had become a household name, a familiar fantasy accessible to the masses.

From Fantasy to Fusion: Chinoiserie’s Modern Revival

In today’s design world, Chinoiserie is back—and it’s not just riding nostalgia’s coattails.

Designers are blending traditional Chinese motifs with minimalist Scandinavian aesthetics, creating serene interiors that nod to history without feeling dated. This modern revival, often dubbed Neo-Chinoiserie, values authenticity while embracing reinterpretation.

_1757385011073.jpg) NEO-CHINOISERIE LIVING ROOM

NEO-CHINOISERIE LIVING ROOM

NGV’s curatorial notes from the exhibition stress this shift from passive appropriation to reflective curation, where Chinese heritage is no longer exoticized but carefully contextualized [NGV Exhibition].

| Luxury hotel suite adorned with hand-painted silk wall coverings. | _1757385484319.jpg) |

| HAND-PAINTED SILK |

We see it in luxury hotels with hand-painted silk wallpapers, in curated homes featuring Ming-style chairs against contemporary backdrops, and in lifestyle brands that respect heritage while reinventing its language.

No more one-size-fits-all dragons. Now it’s all about storytelling.

A Style That Connects and Questions

So, what does Chinoiserie mean in 2025? It's not just peonies on wallpaper or porcelain on a shelf. It’s a mirror—sometimes foggy, sometimes clear—reflecting centuries of fascination, misunderstanding, and admiration.

Sure, it began as a Western idea of what China “looked like.” But over time, it became a style that provoked conversations about identity, heritage, and cultural exchange. It made people ask:

Who gets to define beauty?

Who gets to borrow from whom?

And what happens when cultures meet—not through conquest or commerce alone, but through curiosity?

_1757397128436.jpg) CHINOISERIE AS CULTURAL BRIDGE

CHINOISERIE AS CULTURAL BRIDGE

As both the USC research and NGV's exhibition emphasize, Chinoiserie reveals just as much about the West’s own desires as it does about its interpretations of China.

In the end, Chinoiserie isn’t just a look. It’s a bridge. And in an increasingly globalized world, those are the things we need more than ever.